Relevance/importance of faceoffs has, somehow, become a “hot” issue in conversation about the Sabres and the NHL. One of our readers decided that he had more to say than Twitter would allow and passed along the following piece about the issue.

There are more words in this post than Trending Buffalo typically use in a month, but it introduces some interesting concepts to the debate.

– – – – – – – – – –

On correlation, causation, and (un)importance of faceoff wins

Guest post by Ben Finkel

Introduction

Introduction

After a recent Twitter conversation with Jeremy White of WGR, I was reminded of how easy it is to make very bad inferences from simple statistical questions. As people, we are generally terrible with statistics. We play the lottery, gamble at the casino, and fiddle with the stock market usually without realizing that we’re just throwing our money away. Even professional media personalities make baldly ridiculous claims on national TV (see responses to Nate Silver on the 2012 Presidential Election) without ever realizing their mistakes. As a self-described numbers nerd this bothers me more than I’d care to admit. When Jeremy White does it on Twitter, with a fairly sizable audience, I’m incapable of controlling myself.

The short version of the conversation goes like this: Jeremy suggested that, until he had statistical proof that faceoff win percentage was important for a team to win, he didn’t think it mattered. It occurred to me that it would be easy to plot a correlation between face-off win percentage and games won since both of those numbers are right on the NHL website. After I did that, I posted a picture of the resulting scatter plot with a fitted line and indicated that, yes, there was a definite positive correlation but it was very small.

Jeremy replied that the correlation wasn’t proven and, even if it were that didn’t prove causation.

@benfinkel @iamguybo and even if correlation all were to be proven (which it isnt) that’s still not causal.

— Jeremy White (@JeremyWGR) March 4, 2013

At this point, my inner Sheldon Cooper started to get agitated. There was too much packed into that statement and the comments leading up to it that was either incorrect or misleading. I hated seeing common mistakes perpetuated by someone with as many followers as Jeremy, and since I already had his attention, I had to keep going. The conversation ended OK, but without a whole lot of additional explanation. Simply put, 140 characters is too few for a good conversation about something as potentially complex and statistical analysis and correlation.

I think that clarification on this topic is important. It’s not hard to understand– only hard to explain, and understanding can be immensely useful for all sorts of topics, even those not related to sports!

Correlation does not imply causation.

You’ve probably heard the phrase “correlation does not imply causation” and you may even have a good idea what it means. It’s still a good starting place and very useful to explicitly highlight what that does and does not mean.

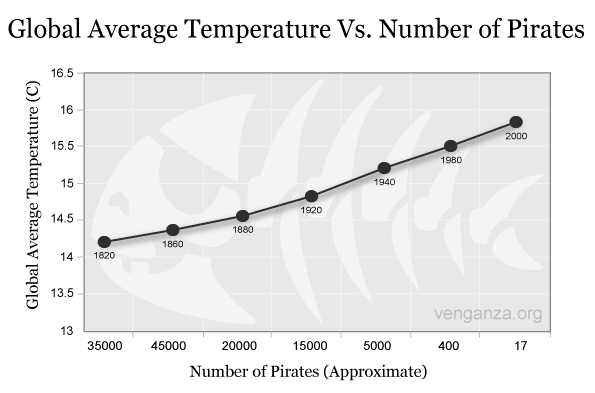

Statistics are used to try to determine if one thing causes another– the nerd term for that being “causality.” The basic point is that just because two “variables” (or metrics, or whatever) change at the same time doesn’t mean that they have anything to do with one another: there is no implied causality between the two. My favorite example is the pirates vs. global temperature graph from the Flying Spaghetti Monster website.

The number of pirates in the world has decreased over the past two-hundred years while the average global temperature has increased. The joke which we all get is that those two things are very likely unrelated and that the presence of pirates wasn’t doing anything to keep global temperatures where they were. The lack of causality goes both ways. Rising temperatures haven’t caused fewer pirates in the world.

It’s important to note that a lack of implication is only that. Two things may or may not cause one another, the question is simply not even addressed in a simple two-variable correlation calculation.

Yes, faceoff wins correlate positively with games won. No, they don’t cause them. Duh.

The data showed that, over the 2010 and 2011 seasons, face-off wins correlated positively with games won with a correlation coefficient of .21. (Just pull the numbers from NHL.com and plug them into Excel if you really want proof of this.) This is definitely a correlation, but a small one. It would be easy to suggest from this analysis alone that faceoffs matter but are probably not as important as a lot of other things.

When Jeremy pointed out that this didn’t prove causation, he was absolutely right. However, he was incorrect that correlation wasn’t “proven.” For the two years of data included in the data set and for all practical definitions of proven, the positive correlation between the two measures was indeed proven to exist. Describing exactly what the data told us requires delving into topics like null hypotheses and confidence intervals and would put most normal people to sleep. Put into a narrative, it’s mostly accurate to say that the positive correlation between the two tells us that for any team in the league if one of those two measures is high it’s more likely than not that the other one will be high as well. In the general case, as I explained above, whether or not one caused the other is a different question that is not addressed in the analysis.

However, that general case disclaimer is redundant because, in the specific case, we can also see that of course faceoffs don’t cause wins. In hockey, only goals cause wins (or goal differential, specifically.) The scoring mechanism for the game doesn’t dish out wins or losses based on faceoff percentage, and the standings don’t take faceoff percentage into account. In fact, this is true of any metric you want to measure other than goals for and goals against. Shots on goal don’t cause wins, nor do hits, or power plays, or hairstyles. Any measure outside of goals can be better described as indicators. They can only be used as a mechanism to guess at how many games a team has won.

It’s still an interesting question and potentially useful.

All of this may lead you to conclude that I don’t think faceoff percentage or any other measure is worth looking at since none of them “cause wins.” That is of course a ridiculous position to end up in (although it’s not uncommon in math to end up pretty deep in the rabbit hole.) Most people would agree that shots and power plays make it more likely you’ll win while hits and hairstyles less so. If those metrics aren’t counted as part of the score, how do they end up being important?

I think the answer comes from deriving wins into these measures. Wins require goals, so a better question might be: Does “it” cause you to score more (or your opponent to score less), “it” being whatever measure we’re talking about. It’s not terribly interesting asking if power plays cause more goals since anyone who watches the game can tell that they probably do. (By no means am I suggesting this is proven, or even not worthy of researching. I think it would be super interesting to try and quantify how much more likely you are to score on the power play versus five-on-five.)

The reason that I find faceoff percentages so interesting is that skill in taking faceoffs doesn’t seem to have anything to do with actually playing hockey and scoring goals.

Think about it– Players spend 99% of the time on the ice skating, shooting, checking, and generally doing other things that constitute “playing hockey.” That 1% of the time they’re taking faceoffs, it’s like we’ve entered a voodoo land where everyone sits still and the puck is in the referee’s hand. Truthfully, you could be great at hockey and terrible at faceoffs (many players are) and vice versa.

When determining whether or not to sign a player when you have limited funds or maybe what to focus on during limited practice time, being able to quantify how you should weigh their face-off skill against their scoring skill becomes a very useful question as well as interesting for fans of the game to mull over.

I don’t have the numbers handy but maybe they’re out there.

All of this is an variation of the general problem of applying “Moneyball” statistical analysis to sports like hockey. Whereas baseball is full of easily identified discrete events, hockey or soccer or basketball have a much more fluid and co-mingled field of play. It’s difficult to affiliate one specific event or characteristic with a specific outcome.

The anecdotal argument has something to do with face-offs giving you more time of possession and thus more time to take shots and score goals, but it is easy to refute that by pointing out that as long as you can quickly win the puck back playing “regular” hockey there’s no need to win the face-off. Simply correlating faceoff wins with goals doesn’t do the trick either: it fails to take into account goals against and the goals could easily have nothing to do with the faceoffs.

The best bet, in my opinion, would be to try to associate specific goals to faceoff wins. How many goals resulted directly from winning a faceoff? The caveat here is that “resulted directly from” is an inherently subjective statement. Even if we could agree on a general definition of that statement, it’s not being measured today. At least, not that I know of. I like to think that professional sports organizations take it seriously and have their own statistical departments that have made an attempt to catalog just how important faceoff wins are to scoring goals and winning games.

But maybe not. After all, the “Moneyball” revolution in baseball wasn’t that long ago. Maybe there is a web community of statistically-minded people out there analyzing NHL footage in order to compile this exact statistic. Maybe they’ll change the game in time, and we’ll all have a better understanding of how faceoffs play into increasing the likelihood of wins. Anyone care to give it a whirl?

So there…Great article!

Good post. In hearing some of Jeremy White’s take on this subject on the radio in recent weeks, I’ve thought that I like his approach and analytical frame of mind, but that he has fallen short with his conclusions. His approach is the right one, but he has simplified it too much. Any statistical analysis determining “winning hockey games” will be multivariate…. You can’t just correlate a bunch of things together and make conclusions. Also, your point about the game of hockey lacking discrete events that yield information is an important one. How do you quantify the effect of any single event when a scoring play is typically a chain of (infinite?) causal events (i.e. faceoff win, defenseman’ decision to skate 1 meter to the left, then his decision to dump the puck off the wall at a 65 degree angle, then the forward’s decision to play the body instead of the puck, etc. etc.)?

It would be an interesting endeavor though to quantify how goals scored could “result directly from” a faceoff win, as you suggest. Are you thinking of something like: “how many goals are scored when the team winning the faceoff retains possession of the puck for an entire shift?’ or something along these lines…? With that approach, I think you would be on the right track of really quantifying the effect of faceoffs, but it would still be difficult to isolate that variable.